The Topkapi Sarayi was the second palace in Istanbul after the conquest. The first was in the Bayezit area and it was called the Old Palace after the construction of Topkapi. Called the New Palace initially it was named as the Topkapi Palace after a summer palace near the sea at Sarayburnu in the 19C.

The construction of the Topkapi Palace, including the walls, was completed between 1465 and 1478. However, different sultans having ascended to the throne added parts to the palace which now gives the appearance of a lack of unity and style. The changes were made for reasons of practicality, to commemorate victorious campaigns or to repair damage caused by earthquakes and fire.

The Topkapi Palace had never been static but was always in the process of organic development with the influences of the time. The first of these influences was the parallelism between the palace and the empire. As the empire became larger, the palace was likewise enlarged. The second is that as the sultans felt insecure and withdrew themselves behind the walls removed from nature, there was an attempt to bring nature inside the walls in the form of miniatures, tiles and suchlike.

If late Ottoman period palaces are excluded, only the Topkapi Palace survived from the glory days of the great Ottoman Empire, which implies that palaces for the Ottomans were something different than the ones we know today. There is a kind of humble simplicity and practicality in the Ottoman palaces.

If late Ottoman period palaces are excluded, only the Topkapi Palace survived from the glory days of the great Ottoman Empire, which implies that palaces for the Ottomans were something different than the ones we know today. There is a kind of humble simplicity and practicality in the Ottoman palaces.

The Topkapi Sarayi was a city-palace with a population of approximately 4,000 people. It covers an area of 70 hectares / 173 acres. It housed all the Ottoman sultans from Sultan Mehmet II to Abdulmecit, nearly 400 years and 25 sultans. In 1924 it was made into a museum.

The palace was mainly divided into two sections, Birun and Enderun. Birun was the outer palace and Enderun the inner. Out of four consecutive courtyards of the palace the first two are Birun. Enderun, the inner palace, consisted of the third and fourth courtyards with the harem.

The first courtyard which was open to the public started after the Bab-i Humayun (Imperial Gate). This was the service area of the palace consisting of a hospital (with a capacity of 120 beds), a bakery, an arsenal, the mint, storage places for various things and some dormitories. This courtyard acted something like a city center.

Topkapi Palace, as well as being the imperial residence of the sultan, his court and harem, was also the seat of government for the Ottoman Empire, Divan. The second courtyard, also called Alay Meydani (Procession Square), which started after the Babusselam (Gate of Peace), was the seat of the Divan and open to anyone who had business with the Divan. This was the administration center. The Divan met four times a week. In the earlier years the sultan would be present at these council meetings, but later on, he would sit behind a latticed grille placed in the wall and listen to the proceedings from there. The Council never knew whether or not the sultan was actually present and listening to them unless he decided to speak himself. The Divan consisted of two rooms: the Office of the Grand Vizier and the Public Records Office, the Tower of Justice.

In addition to the Divan there were also the privy stables and kitchens. The kitchens consist of a series of ten large rooms with domes and dome-like chimneys. In these kitchens in those times they cooked for about 4,000 people. The kitchens were used separately for different people, because different dishes for different classes had to be prepared.

In the kitchens today, a collection of Chinese Porcelain which are accepted as the third most valuable in the world, are on display together with authentic kitchen utensils as well as both Turkish and Japanese Porcelain.

Just before entering the third courtyard, in front of the third gate, the Babussaade (Gate of Felicity) or the Akagalar (White Eunuchs) Gate is the place where the throne was placed for all kinds of occasions, such as religious holidays, welcoming foreign ambassadors and funerals. Payment of the Yeniceri salaries took place there too as well as the handing over of the sancak, the standard or the flag of the Caliph by the sultan.

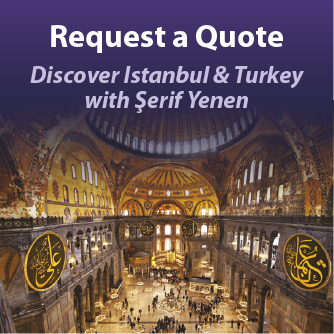

The Enderun, inner palace, started after the Babussaade and was surrounded by the quarters of the inner palace boys who were in service to the sultan and the palace. The first building after entering into the third courtyard is Arz Odasi, the Audience Hall. Many important ceremonies also took place there. Foreign ambassadors and results of Divan meetings were presented to the sultan in this chamber.

In the middle of the courtyard is the library of Sultan Ahmet III. On the right is a section in which sultans’ costumes are shown. Next to this is the treasury section where many precious objects are displayed. Among these the Kasikci Diamond (the Spoonmaker’s Diamond) and the Topkapi Hanceri (the Topkapi Dagger) are the most precious. The Kasikci Diamond is 86 carats, “drop-shaped”, faceted and surrounded by 49 large diamonds. The Topkapi Dagger, a beautiful dagger ornamented with valuable emerald pieces was planned to be sent to Nadir Shah of Iran as a present, but when it was on the way it was heard that Nadir had been assassinated and so it was taken back to the palace treasury. Relics including a hand, arm and skull bones belonging to John the Baptist are also on display in the treasury section.

From the right-hand corner to the left in this courtyard are the sections of miniatures, calligraphy, portraits of sultans, clocks and holy relics of Islam. The holy relics are personal belongings of the Prophet Mohammed (a mantle, sword, seal, tooth, beard and footprints) and Caliphs, Koran scripts, religious books and framed inscriptions.

In the fourth courtyard there are pavilions some facing the Marmara Sea and others facing the Golden Horn.

Life at the Court

The focal point of the court was the sultan, of course. The sultan’s daily life was very simple. In addition to daily regular activities, sultans, in order to broaden their perspectives, gathered scholars, poets, artists and historians at the palace. Most of the sultans in the Ottoman Empire united many skills in themselves. They commissioned new works, manuscripts and bindings, were ardent readers, competent calligraphers, poets, archers, riders, cirit (javelin) players, hunters, composers, etc.

In daily life at the palace, silence was dominant. Hundreds of people tried not to meet the sultan unless they needed to and in keeping voices down, it was even said that, people of the court sometimes developed a body language system among themselves.

The Harem

The concept of the harem has provoked much speculation. Curiosity about the unknown and inaccessible inspired highly imaginative literature among the people of the western world. People always basically thought that in a harem there were hundreds of beautiful girls and a sultan who had fun with all of them. This is generally not correct as the sultan could not, perhaps unfortunately for him, just leap into a roomful of beauties and have his way. There were certain rules with life in the Harem.

The word harem which in Arabic means “forbidden” refers to the private sector of a Moslem household in which women live and work; the term is also used for women dwelling there. In traditional Moslem society the privacy of the household was universally observed and respectable women did not socialize with men to whom they were not married or related. Because the establishment of a formal harem was an expense beyond the means of the poor, the practice was limited to elite groups, usually in urban settings. Since Islamic law allowed Moslems to have a maximum of four wives, in a harem there would be up to four wives and numerous concubines and servants. Having a harem, in general, was traditionally a mark of wealth and power. Though the women of the harems might never leave its confines, their influence was frequently of key importance to political and economic affairs of the household, with each woman seeking to promote the interests of her own children.

The most famous harems were those of the sultans of the Ottoman Empire. The harems of the Ottoman Turkish rulers were elaborate structures concealed behind palace walls, in which lived hundreds of women who were married, related to, or owned by the head of the household.

The Harem of the Sultan

The idea of the harem came to the Ottoman sultans from the Byzantines. Before coming to Anatolia, Turks did not have harems. After the conquest of Istanbul, sultans built the Topkapi Palace step by step. Parallel to it, a harem was also begun. Eventually it became a big complex consisting of a few hundred rooms. The harem was not just a prison full of women kept for the sultan’s pleasure. It was his family quarters. Security in the harem was provided by black eunuchs. Valide Sultan (Queen Mother) was the head of the harem. She had enormous influence on everything that took place there and frequently on her son too.

Young and beautiful girls of the harem were either purchased by the palace or presented to the sultan as gifts from dignitaries or sultan’s family. When these girls entered the harem, they were thoroughly assessed.

Among the girls there were mainly four different classes: Odalik (servant), Gedikli (sultan’s personal servants; there were only twelve of them), Ikbal or Gozde (those were Favorites who are said to have had affairs with the sultan), Kadin or Haseki Sultan (wives giving children to the sultan). When the Haseki Sultan’s son ascended to the throne, she was promoted to Valide Sultan. She was the most important woman. After her, in order of importance came the sultan’s daughters. Then came the first four wives of the sultan who gave birth to children. Their degree of importance was in the order in which their sons were born. They had conjugal rights and if the sultan did not sleep with them on two consecutive Friday nights, they could consider themselves divorced. They had their own apartments. The Favorites also had their own apartments. But others slept in dormitories.

Girls were trained according to their talents in playing a musical instrument, singing, dancing, writing, embroidery and sewing. Many parents longed for their daughters to be chosen for the Harem.

It should not be thought that women never went out. They could visit their families or just go for drives in covered carriages from which they could see out behind the veils and curtained windows. They could also organize parties up on the Bosphorus or along the Golden Horn.

Kizlar Agasi (Chief Black Eunuch) had the biggest responsibility and was the only one who knew all the secret desires of the sultan. Eunuchs, owing to different methods used for castration, were checked regularly by doctors to make sure they remained eunuchs.

When a sultan died, the new sultan would bring his new harem which meant that the former harem was dispersed. Some were sent to the old palace, some stayed as teachers or some older ones were pensioned off.

Yeniceriler (Janissaries)

Janissaries (Turkish yeni is new and ceri is a soldier), standing Ottoman Turkish army, were organized by Murat I. Ottoman armies had previously been composed of Turkoman tribal levies, who were loyal to their clan leaders, but as the Ottoman polity acquired the characteristics of a state, it became necessary to have paid troops loyal only to the sultan. Therefore, the system of impressing Christian youths (devsirme) was instituted and having been converted to Islam and given the finest training, they became the elite of the army. Special laws regulated their daily life cutting them off from civil society such as being forbidden to marry. Devotion to such discipline made the Janissaries the scourge of Europe. These standards, however, changed with time; recruitment became lax (Moslems were admitted, too) and because of the privileges Janissaries enjoyed, their numbers swelled from about 20,000 in 1574 to some 135,000 in 1826. To supplement their salaries, the Janissaries began to pursue various trades and established strong links with civil society, thus undermining their loyalty to the ruler. In time they became kingmakers and the allies of conservative forces, opposing all reform and refusing to allow the army to be modernized. When they revolted in 1826, Sultan Mahmut II dissolved the corps by proclamation, putting all opposition down by force. Thousands were killed and others banished, but most were simply absorbed into the general population.

Tugra (Monogram of a sultan)

Each sultan had a personal emblem called a tugra, a calligraphic arrangement of the letters of his name and titles. They were used at the top of imperial decrees or in the inscriptions of buildings (gates, mosques, palaces, fountains etc.).

Sultans and the Caliphate

The Caliphate is the office and realm of the caliph as supreme leader of the Moslem community as successor of the Prophet Mohammed. Under Mohammed the Moslem state was a theocracy, with the Seriat, the religious and moral principles of Islam, as the law of the land. The Caliphs, Mohammed’s successors, were both secular and religious leaders. They were not empowered, however, to promulgate dogma, because it was considered that the revelation of the faith had been completed by Mohammed.

In 1517, when Sultan Selim I captured Cairo, he also added the title of caliph to that of sultan. After that, all Ottoman sultans automatically became caliphs when they ascended to the throne.

The title held little significance for the Ottoman sultans until their empire began to decline. In the 19C, with the advent of Christian powers in the Near East, the sultan began to emphasize his role as caliph in an effort to gain the support of Moslems living outside his realm. The Ottoman Empire collapsed during World War I. After the war, Turkish nationalists deposed the sultan and the Caliphate was finally abolished in 1924 by the Turkish Grand National Assembly.